“If these decorative porcelains of Hung-hsien are seen side by side with similar ones of T’ung-chih, Kuang-hsü or Hsüang-t’ung, the progress in the art of the potter cannot be denied. The white of the porcelain body has reached the state of pureness for which the Chinese reserved the name ch’un pai. The enamels are clear, brilliant and translucent. The body of eggshell equals any Ch’ien Lung or Yung-cheng ware. Hung-hsien porcelain has acquired an identity of its own which sets it apart from former and from later periods. Though the political aims of Yüan Shih-k’ai failed, as far as porcelain is concerned his period of reign cannot be deleted from the history of art. During his reign this old and traditional Chinese art apparently reached its last apogee.“

-H.A. van Oort, The Porcelain of Hung-Hsien, 1970, p. 160.

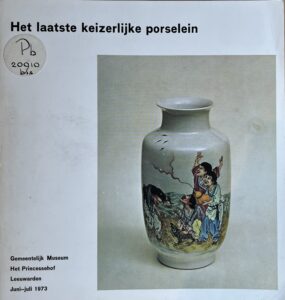

A fine and rare grisaille-enameled ‘river landscape’ vase, iron-red Hongxian nian zhi four-character seal mark within a double square and possibly of the period or Republic Period, ca. 1915-1930.

Provenance:

Formerly in the Georg Weishaupt collection, exhibited at the Museum für Kunsthandwerk, Frankfurt am Main, June 25 to August 13, 1987, and exhibited at the Museum für Kunsthandwerk, Berlin, Autumn 1987, illustrated in Vom Schatz der Drachen / From the Dragon’s Treasure (Gunhild Avitabile, 1987), pp. 132-133, no. 184.

Sold at Sotheby’s Amsterdam, The Weishaupt Collection of 19th and 20th Century Chinese Porcelain, 16th October 1995, lot 157, p. 46 / p. 49.

Private collection, The Netherlands.

The same vase as illustrated in Vom Schatz der Drachen / From the Dragon’s Treasure (Gunhild Avitabile, 1987), p. 133.

Upon acquiring the fine ‘landscape’ vase pictured above with a Hongxian mark and remarkable provenance, we were inspired to write a blog post about this extraordinary piece, digging deeper into this interesting and mysterious subject. This post will include a detailed description of the vase, a closer look into the provenance and previous owner, an exploration of the intriguing scholarly debate over the authenticity of Hongxian marks as period pieces, a brief overview of the porcelain industry during this era, and a history of Yuan Shikai’s fascinating journey as president of China becoming emperor Hongxian, only to become president again and dying soon after.

Let’s take a closer look at this vase first. When first handling the piece, I was surprised by the relatively light weight of 1081 grams in comparison to the height of 27 cm. An interesting feature which is talked about in Zhao Ruzhen’s book Guwan zhinan “A Guide to Antiques”, Beiping 1942:

‘Because the body of the porcelain was very thin, the breakage rate during manufacture was very high, so that the number of perfect pieces in the end was not large.‘

Another striking feature is the whiteness of the body and the purity of the glaze, both elements seen in all high-quality Hongxian and Juren Tang marked pieces.

The fine craftsmanship becomes even more evident when looking at the intricate landscape painting that adorns the vase. The exquisitely decorated scene is done in a painterly style as if it were a scroll painting. The brushwork is both delicate and deliberate, showcasing a mastery of traditional techniques. The subtle gradations in color and texture create a sense of depth and movement, as can be seen when looking the grisaille-enameled rockwork and trees on the foreground, painted with hard and strong brushstrokes, creating a sense of depth to the softer and more delicately painted background scene and as a result drawing the viewer into the serene scenery. This level of detail not only highlights the skill of the artisan but also aligns with the high standards of Hongxian-era porcelain production.

There is a striking comparison in the style of painting the gnarly trees, the rockwork and figures when looking at these two mirrored-pair vases in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, accession numbers 68.4.1 and 68.4.2.

Vases and bowls produced during or shortly after the Hongxian reign were often made as mirrored pairs, a concept further clarified by H.A. van Oort:

“From the production of those days an increasing preference can be noted on the part of porcelain painters for drawing symmetrical designs on pairs of vases and bowls. Most ‘pairs’ of the K’ang-hsi, Yung-cheng and Ch’ien-lung porcelains consist of two identical ones. The closer they resemble each other the better they are. Hung-hsien pairs are often symmetrical pairs, which means that they are opposite of each other, as if they were reflected in a mirror. Apparently simple, the two-dimensional drawing and painting was hereby given a three-dimensional relation. It is an indication of an increased sense of composition.

-H.A. van Oort, The Porcelain of Hung-Hsien, 1970, pp. 163-164.

In this matter it is interesting to note that a vase with identical shape and decoration but mirrored in design, from the collection of Hugh M. Moss, was illustrated on the cover of Arts of Asia magazine, Vol. 7, Number 2, March – April 1977 (see images below). Could the vase in our collection be its mirrored partner?

HONGXIAN MARKS

In this Arts of Asia article, written by Mark Chou, the author talks about the various marks on Hongxian porcelain:

“The porcelain supposed to have been produced under the regime of Yüan Shih-k’ai (president of China between October 16, 1913 and January 1, 1916 and from March 22, 1916 until his death on June 6, 1916, and emperor from January 1st until March 22, 1916), whose reign title was Hung Hsien, may be marked with four different marks: Chu Jen T’ang Chich (made for Chu Jen T’ang), Hung Hsien Yü Chih (made on the imperial order of Hung Hsien), Hung Hsien Nian Chih (made on the reign of Hung Hsien), or, very rarely, Hung Hsien Yuan Nien (first year of Hung Hsien).”

These Hongxian marks were classified in a methodical system by H.A. van Oort, the vase from our collection is marked Hongxian Nian Zhi in iron-red within a double square, typified by van Oort as type II:

“Type II, red nien-hao within a double red square

The porcelains of type II show a marked superiority in quality when compared to those of the previous type. The body is often whiter, more regular, more even and thinner. The painting is clear and fine. On the whole, objects in this group bear comparison with any good product of Ch’ien Lung. It is useful to draw attention to the fact that vases of this type are probably made by hand and not in moulds, as they often were during the 18th century. Even vases of a rather simple shape seem to have been made by hand on the potter’s wheel.

In contrast with type I, the objects of the second type show less variation as far as quality is concerned. Most porcelains in this decorative group were probably never intended as objects for use, but rather as objects to embellish a room, a studio, a palace-hall or garden pavillion.

Reverting to the type II group with the Hung-hsien nien chih marks, it can be stated without reserve that usually the quality is surprisingly good. Not only of the porcelain but of the painting too.”

-H.A. van Oort, The Porcelain of Hung-Hsien, 1970, pp. 163-164.

In the case of marks on Hongxian porcelain in light of the vase from our collection it is interesting to compare it with another pair of ‘river landscape’ vases done in grisaille with touches of red, gifted by Queen Mary to the Victoria and Albert Museum (accession numbers: C.567-1925 and C.567A-1925), bearing an iron-red “Juren Tang” mark within a double square and the other with an iron-red Hongxian mark. The pictures on the V&A website aren’t really sharp, therefore we encourage you to look up the photo of these vases in Rose Kerr’s book and take a look at the strong similarities in style of painting.

For more on these vases please read:

Rose Kerr, Chinese Ceramics – Porcelain of the Qing Dynasty 1644-1911, V&A, 1998, pp. 128-129, no. 115.

H.A. van Oort, The Porcelain of Hung-Hsien, 1970, p. 256, no. 38. / H.A. van Oort, Chinese porcelain of the 19th and 20th centuries, 1977, pl. 153.

SCHOLARLY DEBATE: MARK AND PERIOD OR REPUBLIC?

Hongxian porcelain remains one of the most contentious subjects in the history of twentieth-century Chinese ceramics, captivating both Chinese and Western scholars alike. According to Jingdezhen taoci shi gao (1959), Yuan Shikai sent Guo Baochang to oversee the production of 40,000 porcelain pieces for “imperial” use, with a total expenditure of 1,400,000 yuan. Some scholars argue that it would have been nearly impossible to produce 40,000 pieces of porcelain within the mere 82 days between late December 1915, when Yuan Shikai adopted the Hongxian reign title, and February 23, 1916, when he was compelled to abandon the monarchy and restore the Republic.

After the demise of the Qing regime the Republic was established, and before long there was the Hongxian ware of Yuan Xiangcheng (Yuan Shikai). Yuan planned to restore the monarchy and according to past traditions, the emperor must commission the manufacture of porcelain to mark the inauguration of his reign. He therefore appointed the porcelain specialist Guo Baochang, who had been in charge of General Affairs in the Office of the President, to be the Superintendent of Excise at Jiujiang, and concurrently to be the Superintendent of Ceramics, in charge of the making of this batch of porcelain. Only the clay material and the labour were to come from Jingdezhen, the colour pigments were to be take from the palace storage. All the wares were to copy Guyue Xuan originals, and they were to have the three-character mark “Juren Tang” written in seal script in red on the base. Because the body of the porcelain was very thin, the breakage rate during manufacture was very high, so that the number of perfect pieces in the end was not large. Each official who had been involved in the project was presented with one piece. When Yuan Shikai was forced to give up the idea of restoring the monarchy, the manufacture of this imperial ware was discontinued. But what had already been made is what is usually referred to as Hongxian porcelain. The Jingdezhen craftsmen took the left-over materials, and with them they made imitations. Of these, the earliest batch was of good quality. As Hongxian porcelain appeared to have an aura about it, the craftsmen decided to put the marks “Hongxian zian zhi”, “Hongxian yu zhi” or “Hongxian yuan nian” on the bases of these pieces in order to enhance their value. The truth is that on genuine Hongxian pieces, there are no marks with the characters Hongxian.”

-Zhao Ruzhen, Guwan zhinan “A Guide to Antiques”, Beiping 1942.

So in short, there are some pieces that can be attributed to the era, although Yuan may have been deceased by the time the order was fulfilled.

According to Simon Kwan, when writing about Hongxian porcelain in his book Brush and Clay, the textual sources have failed to help us settle the question of Hongxian porcelain:

The decoration on this type of enamel-decorated porcelain, so called Guyue Xuan, made in the heyday of the Qing period, took as its subjects landscapes, birds and flowers, hall and pavilions, and themes alluding to peace and prosperity – all designed to reflect the achievement of the dynastic house. These were the very subjects which Yuan Shikai was determined to copy. On the so-called Hongxian-porcelain, however, the subjects are peonies, the god of longevity, scenes from folk tales, children at play, and so on – all subjects popular with the common people and suitable for display purposes in middle-class homes. They would not have been suitable for the inauguration of an emperor. Most pieces with a Hongxian mark have no inscriptions, and the occasional inscription would be of general import and not, like those on Guyue Xuan, of a laudatory nature. What is more puzzling is that there appear to be no copies of Guyue Xuan with either the Hongxian mark or the Juren Tang mark. For that reason, we cannot help but doubt the accuracy of the statements in Jingdezhen taoxi shi gao and Guwan zhinan, and even the statements of Zhang Wanli. All three sources affirm that Guo Baochang had supervised the making of a certain number of enamel-decorated pieces copied from Guyue Xuan. But these sources are not sufficient to enable us to identify the actual pieces of porcelain.

-Simon Kwan, Brush and Clay – Chinese Porcelain of the Early 20th Century, 1990, p. 49.

In the end of this section, Kwan sums up the following conclusions:

” 1 In or around 1916 Guo Baochang did supervise the making of a certain amount of porcelain in Jingdezhen on behalf of Yuan Shikai.

2 We cannot ascertain what mark or marks were used on this porcelain. The probability of “Juren Tang” is quite high, but the possibility of “Hongxian nian zhi” can not be ruled out altogether.

3 The common run of Hongxian ware that we see were made in the years between 1925 and 1930.

4 All pieces with the “Hongxian yu zhi” mark are forgeries.”

-Simon Kwan, Brush and Clay – Chinese Porcelain of the Early 20th Century, 1990, p. 51.

A SHORT HISTORY OF YUAN SHIKAI

A picture of Yuan Shikai in 1913.

Yuan Shikai (1859–1916) was a pivotal figure in Chinese history, playing a central role in the transition from the Qing dynasty to the Republic of China. Born into a well-connected family in Xiangcheng, Henan province, Yuan embarked on a military career, gaining prominence for his success in Korea as a commander during the late 19th century. He later became a key figure in modernizing the Qing military, introducing Western-style reforms to create China’s first modernized army, the Beiyang Army.

Yuan’s influence extended into politics, where he was instrumental in the Qing court’s attempts at reform during its final years. After the 1911 Revolution led to the fall of the Qing dynasty, Yuan negotiated the abdication of the last emperor, Puyi, in exchange for becoming the first president of the newly formed Republic of China in 1912.

Although his presidency began with widespread support, Yuan’s authoritarian rule and power consolidation quickly alienated political rivals and reformists. In 1915, he declared himself emperor of the short-lived “Empire of China,” a move that triggered widespread rebellion and led to the swift collapse of his regime. Humiliated and politically isolated, Yuan abdicated in 1916 and died later that year, leaving China fragmented and on the brink of the Warlord Era.

Funeral procession of Yuan Shikai in 1916.

Yuan Shikai remains a controversial figure, remembered both for his efforts to modernize China and for his failed imperial ambitions, which many view as a betrayal of the republican ideals he initially supported.

THE ORDER OF THE HONGXIAN EMPEROR

The President of the Chinese Republic Yuan Shikai, on December 11, 1915 in China, on the brink of ascending the Imperial throne. (Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images).

Yuan Shikai, driven by ambition, was unlikely to settle for anything less than the maximum. Believing himself on par with the great emperors of China’s past, he carefully orchestrated his rise through strategic dealings with generals, diplomats, foreign powers, and his military. On December 12, 1915, Yuan proclaimed himself Emperor and ascended the Imperial throne. True to tradition, each emperor’s reign required a title, or nianhao. Yuan chose the title Hongxian, meaning “The Grand Constitutional Era.”

Second to left; Yuan Shikai as emperor Hongxian in 1915.

However, his assumption of the throne provoked nationwide outrage. Facing overwhelming resistance, Yuan was forced to abdicate on March 22, 1916, after a mere 82 days on the throne, without even completing the inaugural ceremony. He died shortly thereafter on June 6, 1916. In keeping with the practices of Ming and Qing emperors, Yuan commissioned porcelain bearing his nianhao to be produced in Jingdezhen. The Ching-te-chen t’ao-tz’u shih-kao provides valuable insights into Yuan’s engagement with porcelain production during his brief reign.

‘At the end of the reign of the Ch’ing dynasty its Imperial factory also stopped its activities. After having entered into the Republican era, Yüan Shih-k’ai deceived the country becoming Emperor, and intended to use Hung-hsien as the title of his reign. In 1916 (the fifth year of the Republic) he changed the name of the former Ch’ing Imperial pottery into ” Office for Supervising Pottery Manufacture” and sent Kuo Pao-ch’ang to Chingtechen to supervise the production of official ware and to have 40,000 pieces baked, including 100 pieces of emulation fa-lan coloured ware, for which he was allowed to spend up to 1,400,000 yüan. By comparison with the above-mentioned expenses for porcelain in 1900, the illegal extravagance involved can now be clearly seen. Hung-hsien, moreover, had no official kiln an had to hire workmen to develop colours and shape designs. The painting of the porcelain was done in the house of Hupei (‘workers’) association. They took Yung-cheng and Ch’ien-lung porcelain as their standard model. The potter was Yen The-i (or Yen Jou-chen). When Yüan Shih-k’ai’s Imperial reign had failed, this department was closed. Now these few old buildings are military barracks. The broken tiles and walls glitter at the sunset between the tall grass. These ruined old buildings are the remnants of the history of the factory; they are going to sink down unnoticed‘.

In short, the ‘river landscape’ vase in our collection reflects the ‘problem’ which arises with Hongxian porcelain. Whether a mark and period-piece or made slightly later between 1925 and 1930, one can only be in awe by the exquisite craftsmanship and artistic detail displayed in its design, embodying the technical sophistication of early 20th century porcelain production.

For more on the subject, see the following literature list:

·Gunhild Avitabile, Vom Schatz der Drachen / From the Dragon’s Treasure, 1987.

·Catalogue Sotheby’s Amsterdam, The Weishaupt Collection of 19th and 20th Century Chinese Porcelain, 16th October 1995.

·Mark Chou, A Discourse on Hung Hsien Porcelain, 1987.

·Mark Chou, Hung Hsien Seal Marks: Which is Genuine?, article in Arts of Asia magazine, Vol. 7, Number 2, March – April 1977, pp. 29-32.

·Simon Kwan, Brush and Clay – Chinese Porcelain of the Early 20th Century, 1990.

·Simon Kwan, Hongxian Porcelain and the Role of Wang Xiaotang, article in Orientations magazine, October 1991, pp. 65-70.

·Soame Jenyns, Later Chinese Porcelain, London, 1973.

·Hepburn Myrtle, Late Chinese Imperial Porcelain, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1980.

·Het Laatste Keizerlijke Porselein, Gemeentelijk Museum Het Princessehof Leeuwarden, Juni-juli 1973.

·Zhao Ruzhen, Guwan zhinan “A Guide to Antiques”, Beiping 1942.

·Jingdezhen taoci shigao 景德鎮陶瓷史稿 . Ed., Jiangxi Light Industry Department, Ceramics Institute, Beijing: Sanlian shudian chuban, 1959.

·W.h. Adgey-Edgar, The Porcelain of Yuan-Shih-kai, article in The Connoisseur, October 1923, pp. 99-105.

·Jerome Ch’en, Yüan Shih-k’ai, London, 1961.

·Innovations and Creations – A Retrospect of 20th Century Porcelain from Jingdezhen, Jingdezhen Ceramic Museum and Art Museum, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2004.

·Sir Harry Garner, The Arts of the Ch’ing Dynasty, article in the Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, 1963-1964, London, 1965.

·Peter Wain, Heavenly Pieces – An Exhibition of Chinese Porcelain of the Early 20th Century, May 8th-15th 1993.

·Georg Weishaupt, Das Große Glück / The Great Fortune – Chinese and Japanese Porcelain of the 19th and 20th Centuries and Their Forerunners, 2002.

·Anthony J. Allen, Allen’s Authentication of Later Chinese Porcelain (1796 AD – 1999 AD), 2013.

·Rose Kerr,